Two Turner Collectors who were Friends of Ruskin

Talks given 20 November 2019

by Marcus Bicknell and Margaret Burr

In the bicentenary year of John Ruskin the talks considered two people who were friends of Ruskin

and who were two of the four (including Ruskin) major collectors of Turner's late watercolours

as well of some of his best oil paintings.

St Cuthbert's Church, Philbeach Gardens, Earls Court, London SW5

A Grade I example of the Arts & Crafts Movement

Talks given 20 November 2019

by Marcus Bicknell and Margaret Burr

In the bicentenary year of John Ruskin the talks considered two people who were friends of Ruskin

and who were two of the four (including Ruskin) major collectors of Turner's late watercolours

as well of some of his best oil paintings.

St Cuthbert's Church, Philbeach Gardens, Earls Court, London SW5

A Grade I example of the Arts & Crafts Movement

Photographs by Noel Treacy

For a copy of Marcus Bicknell's talk: Elhanan Bicknell - Turner Collector click here

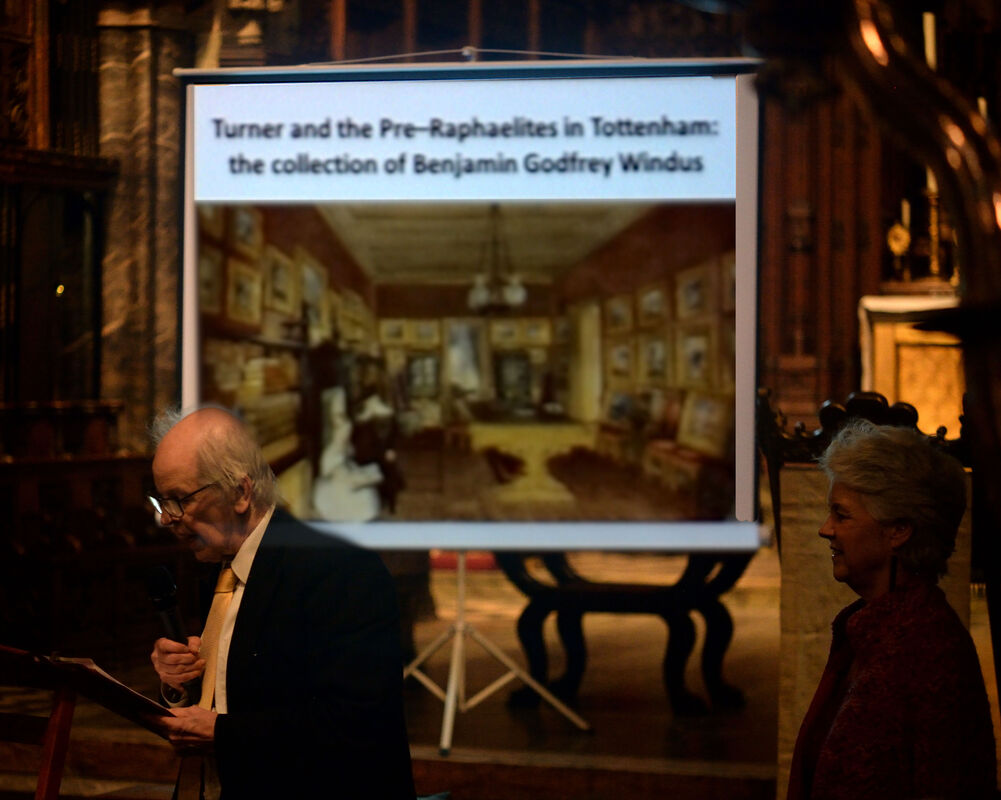

Margaret Burr's talk provided the background to where BG Windus lived, his inheritance, his importance as a collector and his relationship with Turner, Ruskin and PreRaphaelite painters. Much of the information can be found on this website.

Introduction to the talks by Dr Selby Whittingham, Secretary of the Independent Turner Society.

Good Evening. I welcome you to our talks this evening.

A word first about what has prompted this event and its rationale. This year is the bicentenary of the birth of John Ruskin. In 1836 at the age of 17 he wrote his first eloquent defence of Turner in response to a critical review of Turner's “Juliet and her Nurse” by the Revd John Eagles in Blackwood's Magazine (of which I have a copy). Eagles was conservative both politically and artistically and looked back to a time “when Turner was great”. Old friends and admirers of Turner also regretted the change in his style from his early works.

Fast forward to 1842. Following a trip to Switzerland Turner proposed making a set of watercolours to be offered for sale. Ruskin, in the catalogue of an exhibition of his Turner watercolours at the Fine Art Society at 148 New Bond Street (at the same address until recently; I have a copy of the catalogue), related what he had been told by Turner's agent, Thomas Griffith, who was both a collector and gentlemanly dealer.

Turner “went to Mr Griffith of Norwood. I loved – yes, loved – Mr Griffith … I was introduced to Turner on Mr Griffith's garden-lawn. He was the only person Turner minded at that time: but my father could not bear him. ...One day … early in 1842, Turner brought” his Swiss sketches “to Mr Griffith (in Waterloo Place, where the sale-room was”. They fixed on the price of 80gs, commission included, for each. “So then Mr. Griffith thinks over the likely persons to get commissions from, out of all England, for ten drawings by Turner!” (Ruskin's sarcasm expressed his feeling that Turner was neglected, “his reputation ...pretty nearly overturned … by Blackwood's Magazine”, and is partly at the root of the modern idea that Ruskin discovered Turner by himself). To continue, “he sent to Mr Munro of Novar, Turner's old companion in travel; he sent to Mr Windus of Tottenham; he sent to Mr Bicknell of Herne Hill; he sent to my father and me.

So we have the prime Turner collectors at that date – the Ruskins, Munro and the two collectors who are the subjects of to-night's talk. There were other collectors of Turner's oils, but they came from Birmingham and other industrial cities, and represented the change in patronage from that by the landed gentry to that by industrialists, mirroring the change in style and subject that art was undergoing.

The Ruskins, Griffith, Bicknell and Windus all came from that commercial world and all were Londoners, and they regularly met for dinners and anniversaries. (Munro, though he had a London house, was a Scottish landowner and also collected old masters, and so was atypical at this date).

In the event Elhanan Bicknell bought two including the Blue Rigi, which fetched a record price a few years ago and now belongs to the Tate. This brings me to our first talk and lecturer, Marcus Bicknell. His family has always taken an interest in their collector ancestor (and it is good to see so many of his family here tonight). And last year Marcus energetically commemorated the centenary of the death of Elhanan's son Clarence, who followed a path partly similar to that of Ruskin, away from his evangelical background, in his case as a follower of the Oxford Movement which later gave birth to this church, and then to scientific pursuits as well as those of an amateur artist. Celebrations included a biography by Valerie Lester, who sadly died last year, which begins with a chapter on his father Elhanan.

At which point I hand over to Marcus.

Good Evening. I welcome you to our talks this evening.

A word first about what has prompted this event and its rationale. This year is the bicentenary of the birth of John Ruskin. In 1836 at the age of 17 he wrote his first eloquent defence of Turner in response to a critical review of Turner's “Juliet and her Nurse” by the Revd John Eagles in Blackwood's Magazine (of which I have a copy). Eagles was conservative both politically and artistically and looked back to a time “when Turner was great”. Old friends and admirers of Turner also regretted the change in his style from his early works.

Fast forward to 1842. Following a trip to Switzerland Turner proposed making a set of watercolours to be offered for sale. Ruskin, in the catalogue of an exhibition of his Turner watercolours at the Fine Art Society at 148 New Bond Street (at the same address until recently; I have a copy of the catalogue), related what he had been told by Turner's agent, Thomas Griffith, who was both a collector and gentlemanly dealer.

Turner “went to Mr Griffith of Norwood. I loved – yes, loved – Mr Griffith … I was introduced to Turner on Mr Griffith's garden-lawn. He was the only person Turner minded at that time: but my father could not bear him. ...One day … early in 1842, Turner brought” his Swiss sketches “to Mr Griffith (in Waterloo Place, where the sale-room was”. They fixed on the price of 80gs, commission included, for each. “So then Mr. Griffith thinks over the likely persons to get commissions from, out of all England, for ten drawings by Turner!” (Ruskin's sarcasm expressed his feeling that Turner was neglected, “his reputation ...pretty nearly overturned … by Blackwood's Magazine”, and is partly at the root of the modern idea that Ruskin discovered Turner by himself). To continue, “he sent to Mr Munro of Novar, Turner's old companion in travel; he sent to Mr Windus of Tottenham; he sent to Mr Bicknell of Herne Hill; he sent to my father and me.

So we have the prime Turner collectors at that date – the Ruskins, Munro and the two collectors who are the subjects of to-night's talk. There were other collectors of Turner's oils, but they came from Birmingham and other industrial cities, and represented the change in patronage from that by the landed gentry to that by industrialists, mirroring the change in style and subject that art was undergoing.

The Ruskins, Griffith, Bicknell and Windus all came from that commercial world and all were Londoners, and they regularly met for dinners and anniversaries. (Munro, though he had a London house, was a Scottish landowner and also collected old masters, and so was atypical at this date).

In the event Elhanan Bicknell bought two including the Blue Rigi, which fetched a record price a few years ago and now belongs to the Tate. This brings me to our first talk and lecturer, Marcus Bicknell. His family has always taken an interest in their collector ancestor (and it is good to see so many of his family here tonight). And last year Marcus energetically commemorated the centenary of the death of Elhanan's son Clarence, who followed a path partly similar to that of Ruskin, away from his evangelical background, in his case as a follower of the Oxford Movement which later gave birth to this church, and then to scientific pursuits as well as those of an amateur artist. Celebrations included a biography by Valerie Lester, who sadly died last year, which begins with a chapter on his father Elhanan.

At which point I hand over to Marcus.

Publicity for the talks on the Turner Collectors:

|

Elhanan Bicknell

Elhanan was the son of a Unitarian schoolmaster and became a rich whaling entrepreneur who lived on Herne Hill, opposite to the Ruskin family, the young John Ruskin becoming particularly friendly with Mrs Bicknell. He was a major collector of Turner's paintings and watercolours in the 1840s. One of the paintings, Palestrina – Composition, (in 1954 bequeathed to the National Gallery by Charles William Dyson Perrins) was probably inspired by the tercentenary of Palestrina and Turner's involvement with the Catholic Embassy Chapels in London. The much prized Blue Rigi was acquired a dozen years ago by the Tate. One of his sons was married to a daughter of David Roberts R.A. (who left some vivid recollections of Turner) and his wife's nephew was Phiz, the subject of a biography by Valerie Lester, who in 2018 published another on Elhanan's son, Clarence, a Puseyite priest, naturalist, champion of Esperanto and founder of the Museo Bicknell at Bordighera. Another son contributed, unhelpfully, to the controversy over the fate of Turner's cottage on Cheyne Walk. Marcus Bicknell (“charming and erudite”) has been manager of the rock band Genesis, a tv satellite executive (“passionate about entertainment and new technology”), producer of a film on Clarence Bicknell, and is a patron of RADA and a racing car enthusiast. His architect brother is a former Master of the Art Workers Guild. His uncle, Peter, was also an architect, organiser of exhibitions on the Romantics and a member of the Alpine Club. https://www.clarencebicknell.com/en/

|

Benjamin Godfrey Windus

Benjamin Godfrey Windus, Citizen and Coachmaker (i.e. a member of the Coachmakers' Company), inherited from a grandfather the recipe for Godfrey's Cordial. A great-uncle was a wealthy Whig MP, Peter Moore, who claimed to be descended from Sir Thomas More. He started in the 1830s building up a large collection of Turner's watercolours, hung in the library of his cottage at Tottenham, opened to the public, which Ruskin said was the main source for his first volume of Modern Painters. He added oils by Turner and the pre-Raphaelites. The cottage has gone, like Bicknell's mansion, though a watercolour of the library with the Turners is in the British Museum. The main memorial to him is at Rodmell, Sussex, where his son-in-law, Pierre de Putron, was vicar, and where he died and was buried; the church has stained glass which he gave. His son was a writer and watercolourist and the sleeping partner in the publishers Chatto & Windus. His daughter wrote a memoir about him and kept the letters he received from Turner and Ruskin. Edward Windus has a film about him in preparation. Margaret Burr, a Tottenham resident and retired teacher, is a popular lecturer and has created a website on the collection of Windus, about whom she has made new discoveries.

www.turnerintottenham.uk St Cuthbert's church website www.saintcuthbert.org |

Organised by Dr Selby Whittingham of the Independent Turner Society